Story of the Burgess Family

For Black History Month, Trinity College recognizes and celebrates members of the community who have made a difference. Read their stories – trailblazers, change makers and community leaders who fought against racism, barriers and challenges of their times.

For Black History Month, Trinity College recognizes and celebrates members of the community who have made a difference. Read their stories – trailblazers, change makers and community leaders who fought against racism, barriers and challenges of their times.

As the College continues our collective work to address anti-Black racism and inclusion, it’s important to reflect on our history and remember those who made a mark within our community and the world. It is also important to continue to share these narratives not only to celebrate incredible achievements, but also to recognize the discrimination faced.

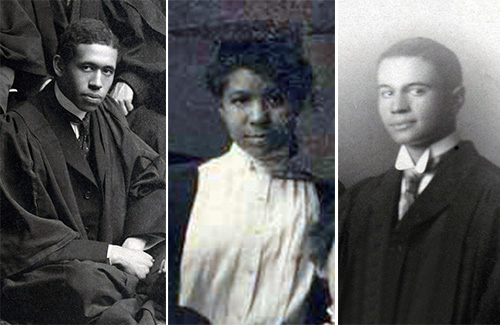

Below is a story of the Burgess siblings from Missouri – (photo) Wilmot, Myrtle and Elmer Burgess – who attended Trinity in the early 1900s. In 2019, Trinity College named a student residence – Burgess House – in St. Hilda’s after our first female Black student, Myrtle Burgess.

By Sylvia Lassom, Rolph-Bell Archivist

In the early 1900s, Provost Thomas Macklem admitted three students to Trinity College and St. Hilda’s College, siblings from St. Louis, Missouri. However, unbeknownst to Provost Macklem when he made the offer of acceptance, the students were Black. Their father – Albert Burgess – was a barrister, and an Anglican. Mr. Burgess had made history when, in 1877, he became St. Louis’ first Black lawyer.

Education was important to their family and all three of Mr. Burgess’s children travelled to Canada to attend Trinity College. Myrtle Burgess (1888-1973), and her older brother Wilmot Burgess (1886-1936) started at Trinity in 1905, until 1909 and 1908, respectively. Their younger brother Elmer Burgess (1890-1976) attended from 1907 to 1910. Of the three Burgesses, Wilmot was the only one to graduate with a Bachelor of Arts degree.

Myrtle Burgess

Class photo below: Myrtle Burgess (back row, second from left)

We know that Myrtle’s application contained testimonials from the Clergy of their Parish and the Bishop of the Diocese where they lived. Her school records were in order. Myrtle – the middle child and only daughter of Albert Burgess – was accompanied by her older brother, Wilmot, when she came to Toronto in 1905. Wilmot had attended high school in Windsor, Ontario, while Myrtle came directly from St. Louis.

The term started in October and in late November Provost Macklem was defending his decision to enroll Myrtle Burgess in a letter to Miss Millie Bennett, a student from Washington DC, who had written to complain about sharing accommodation in St. Hilda’s College with a person of colour.

In Provost’s Mecklem’s response to Millie, he admitted that he likely would not have admitted Myrtle had he known that she was Black, but since she was admitted he would not, as a Christian and a British subject, expel her based on her race. A copy of the Provost’s letter from November 21, 1905 is transcribed below. Although an articulate and measured defence of Myrtle’s right to attend the College, it also offers an important glimpse into the discrimination people of colour faced in the early 20th century. It is a credit to Myrtle’s intelligence, drive and tenacity that even in the face of injustice, she continued her studies at Trinity College. A copy of the full letter remains in the Trinity College Archives:

“I knew nothing of the colour of Miss Burgess until after I had accepted her as a resident student of St. Hilda’s College. I had admitted her on the strength of the best possible testimonials as to her character etc. from the Clergyman of the Parish, and the Bishop of the Diocese where she lives. […] Accordingly, we have now to deal with Miss Burgess, not as an applicant for admission to St. Hilda’s College, but as a student who has been admitted in regular course after due compliance with all the requirements.

Now, as I need hardly remind you, it is not consistent with the principles of British justice, or with the teachings of our Christian religion, to make any person suffer persecutions on account of his colour. Equal rights are by British law accorded to, and by the teachings of the Bible demanded for, all persons alike irrespective of colour. Miss Burgess having been admitted to residence in a country where the Union Jack waves as a symbol of these British rights, and in an institution – which exists for the exercise and inculcation of the principles and teachings of the Christian religion, is clearly entitled to claim exemption from any discrimination against herself on the grounds of colour. If she should prove herself in other respects unworthy of the privilege of residence in St. Hilda’s College, she will doubtless be required to leave the College, as others not of her colour have been required to do before her, and as others of whatsoever colour may be required to do in the future. But if the only charge is that she is coloured, it is not at all likely that she will be asked to leave. If any of her fellow Collegians do not wish to remain there with her they are at liberty to withdraw when they will. I venture to hope, however, that no member of the College will be so unmindful of the foundation on which it is erected, and of the obligations of the Christian religion which all of us profess, as to deny the truth of equality of all person.”

A deeper dive into the archives and the internet has fleshed out the story of Myrtle Burgess. The St. Hilda’s Chronicle records in the spring issues of 1906 that Miss Burgess performed a piano solo, and an instrumental duet with Miss Kammerer at the annual opening meeting of the Literary Society. A programme following the business meeting of the same society featured an instrumental offering by Miss Burgess, and a vocal solo by Miss Bennett, so it seems some sort of civility was observed. However, there were no further musical contributions by Miss Burgess. The Annual Report for St. Hilda’s College for the year 1905-1906, presented by the Principal, Mabel Cartwright, noted that three students had left residence, including “Miss Burgess, for the study of music in which she is particularly gifted.” While she remained registered at St. Hilda’s, paying incidental fees for the next couple of years, she apparently shifted the focus of her studies to the Toronto Conservatory of Music, from which I believe she graduated in 1909. A Saturday Night article from March 6 of that year mentions that she played Chaminade’s ‘Les Sylvains’ at the weekly recital in the Conservatory Music Hall. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to discover where she lived after she left St. Hilda’s; perhaps she boarded with a local Black family.

Wilmot and Elmer Burgess

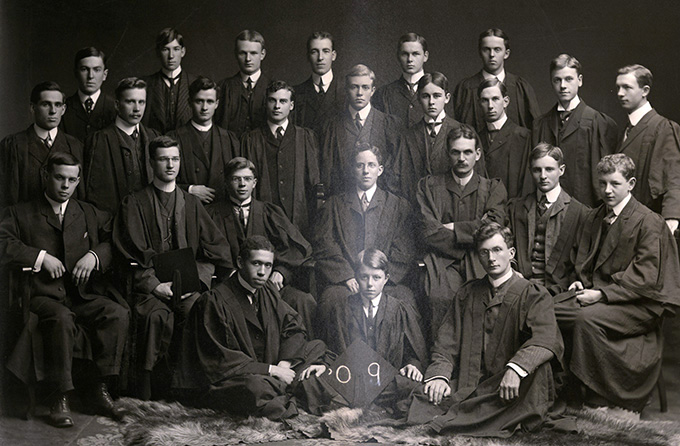

Class of 1909 below: Wilmot Burgess (sitting lower left)

Wilmot Burgess may have integrated more smoothly. His graduation entry in the 1908 Torontonensis reads: “He is a most agreeable companion and like all the other men in his year plays football in the inter-year rugby games.” The Review records that he took part in Steeplechase (February 1907).

Younger brother Elmer Burgess arrived in 1907 and stayed until 1910, but he did not receive a degree. Elmer also played Rugby (Review, Dec 1907), but given his later profession as a physical education instructor, a larger presence in the College athletics scene might have been expected. The brothers lived at Trinity College during their time at the school.

Incoming Class of 1911 below: Elmer Burgess (top right)

After Trinity College

After leaving Trinity College the Burgess siblings carried on with careers in education. Myrtle was employed by Howard University in Washington DC for the 1910-11 term as a piano instructor. For some time, she taught music at the Lincoln Institute, Jefferson City Missouri. The Lincoln Institute, now Lincoln University, was founded after the Civil War to educate the Black citizens of Missouri. In the 1914, St. Louis city directory she is listed as a resident at 218 West Elwood Street, the family home. City directories consistently list her as a piano teacher at that address and later at 3817 Cook Avenue when the family moved to a larger house sometime in the 1920’s.

Wilmot continued his studies during summer sessions at the Universities of Illinois and Wisconsin. He became a teacher within the segregated public school system, including a stint at the Clark Street High School in Evanstown, Indiana. During WWI he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was deployed to France from 1918 to 1919. Most of his career was spent in St. Louis, where he was the principal of several Black schools from 1920 until his death in 1936 at the age of 50. Like Myrtle, he lived at home with his family.

Image: Wilmot Burgess (top right) served in the First World War

Elmer continued his studies after Trinity at the International YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts (later Springfield College), a degree granting institution famous as the birthplace of basketball. Elmer graduated in 1913 and was an active alumnus until his death. He stayed on the east coast for a time, teaching gymnastics and folk dancing and becoming a member of the American Physical Education Association. He also enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving as a Physical Instructor in the American Expeditionary Forces. By 1920 he was briefly back in St. Louis, but soon departed for Baltimore where he joined the Black public school system, first as an Assistant Physical Education Supervisor, then as a supervisor. Around 1928 he married Ruth Wilkins, a fellow teacher. He was on the Board of Directors of a savings and loan association, and was much celebrated when he retired in 1959, a year after his wife died.

The Burgess Family

Around 1965, Myrtle moved to Baltimore; the two surviving members of their family shared Elmer’s home. She suffered a stroke in 1970 and died in 1973; Elmer lived until 1976.

One interesting story emerged about the Burgess family from a digital exhibit from Washington University. In 1923, Mr. Burgess picked up season’s tickets for his sister and noticed that the tickets had been transferred to the last row of a different section than the seats she had selected, and where she had sat the previous year. Mr. Burgess protested but was not successful in changing the seat assignment. The Minutes of the Executive Committee of the St. Louis Symphony Society reveal that complaints had been made by audience members being forced to sit next to Negroes. In response the Committee voted in a policy to segregate Black patrons.

Albert Burgess, the family patriarch, struggled to obtain his law degree in the years following the Civil War. He was active in civic affairs and in 1894 the Mayor of St. Louis appointed him Assistant City Attorney. No doubt he had high hopes that racial barriers would decline as time went by. It’s likely that he close Toronto as a place to educate his children with the expectation that life would be easier for them in Canada. I’m not sure he was right.

Categories: Alumni; College News; Discover Trinity